About me: Maria A. Gutierrez, PhD student at the University of Cambridge. Supervised by Prof. Julia Gog. (My contact details are here.)

Update: I originally created this poster for the 2022 Cambridge Infectious Diseases Annual Symposium. I am now using this poster for the JUNIPER Research Meeting in March 2022. Below this paragraph is the content as it was during the CID conference. There will hopefully soon be a preprint on the same topic, explained in more detail.

Evolutionary pressure of vaccine-induced mutation probability

Email: mag84@cam.ac.uk , Maria A. Gutierrez (PhD student)

Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics (DAMTP) & King’s College.

Acknowledgements: Prof Julia Gog OBE (PhD supervisor) and Gates Cambridge (Scholarship)

Click here for poster display. (Design partially inspired by this video)

CONTENTS:

– 0. Abstract

– 1. Introduction

– 2. Conceptual framework

– 3. Methods

– 4. Results

– 5. Discussion

– References

0. Abstract

Vaccines have been key in controlling the Covid-19 pandemic through the reduction in the number of cases and deaths, but they will likely also play a role in viral evolution. The long-term dynamics of the pandemic depend strongly on the evolutionary trajectory that the virus will take. In this mathematical study, we show that depending on the contribution of breakthrough cases (in vaccinated hosts), then either (i) vaccination is always good to reduce evolutionary pressure, or (ii) intermediate levels of vaccine coverage are the worst for evolutionary pressure. These results depend quantitatively on the vaccine efficacy for transmission blocking, which, if sufficiently high for a given R0, allow eradication of the disease at a large enough vaccine coverage.

1. Introduction

The appearance and rapid growth of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 at the end of 2021, which is less severe, more transmissible, and partially escapes the current vaccines, has emphasized how much the long-term dynamics of the Covid-19 pandemic will depend on the evolutionary trajectory of the virus. The antigenic properties with respect to existing immunity (either natural or vaccinal) of future variants will be particularly important in this aim. As vaccination campaigns progressed through high-income countries in the first half of 2021, concerns arose about how vaccination strategies could exert selection pressure and increase the risk of new antigenic variants [1], [2], [3].

In the so-called 2004 “Phylodynamics” paper, Grenfell et al [4] link the level of immune pressure to the within-host adaptation potential of a virus. Higher immune pressure decreases viral abundance but increases the strength of the selection in favour of antigenic escape. Hence, they argue that intermediate levels of immune pressure are the most likely to give rise to an antigenic escape variant. More generally, this trade-off results in the parabolic shape shown above (Fig 2.A of their paper).

This static phylodynamic model assumes that there is no adaptation rate in naive hosts -point (1) in the diagram- because there is no effective response. This is a limitation of this model for some virus, because mutations that favour antigenic escape can occur in previously naive hosts. They will also have some level of selection in favour of immune escape variants, since their adaptative immune system would also be building immunity and antibodies against the original variant that infected the host will be present in the later part of the infection. Furthermore, even if this selection of immune response is low (due to delayed adaptative immunity), an antigenic escape variant may also be selected for in a naive host due to other advantageous properties (eg, increased replication rate) that increase its intrinsic within-host fitness relative to the original variant that infected the host. In our work, we let the cases in unvaccinated individuals (and previously naive) contribute non-trivially to the probability that a mutation arises.

2. Conceptual framework

We define the escapiness p of a pathogen as the probability that an infected individual. generates a variant of the pathogen that reaches a sufficient population size for it to be passed into other hosts. Note that:

- Escapiness depends on the characteristics of the variant(s) we are interested in considering. For example, a variant less fit than the original variant and without any antigenic advantage would have very little chance of reaching a sufficient viral load.

- This definition does not require the new variant to be an antigenic escape variant, though it is the motivation for its definition.

- Escapiness depends on the individual through immune status: through vaccination as we will discuss below but also more broadly on their immune system (in SARS-CoV-2, immunocompromised hosts are more likely generate variants).

We define the escapiness effect θE of a pathogen and a vaccine against it to be the ratio of the escapiness in a vaccinated individual to the escapiness in the same individual were they not vaccinated.

- Escapiness effect is somewhat analogous to vaccine efficacy parameters (VEs) against for susceptibility, severe disease, or other outcomes.

- However, there is no guarantee that vaccination has a positive effect at the within-host level from an evolutionary point of view. It may well be the case that θE >1, hence the word “effect” which is neutral towards which direction vaccinations act, instead of “increase”, “deacrease” or “efficacy”.

Finally, we define the evolutionary pressure P of an epidemic in a population to be the probability of emergence of a new variant. We will implicitly have in mind a vaccine escape variant (i.e., a variant that evades the immunity from the deployed vaccines), and hence we will use the term (vaccine) escape pressure interchangeably.

3. Methods

We assume that the evolutionary pressure depends linearly on the number of cases in the population. This follows from a Taylor expansion of Thompson et al. [2]:

where p is the individual probability of a variant arising during infection and N is the total number of cases in the population. We, however, associate different weights to cases depending on the vaccination status of the host (vaccinated or not), similarly to some of the examples considered in the Supplementary Information of Gog et al. [3], and we treat their relative weight continuously, through our escapiness effect parameter θE.

This leaves the total (population-level) probability of an escape variant arising in an epidemic as P=p(Nunv+θENvac) where Nunv and Nvac are the numbers of cases in vaccinated and unvaccinated hosts, respectively, and p is the escapiness of the virus (the probability of a variant arising during infection in an unvaccinated host).

For simplicity, in the plots shown below we worked with a transient epidemic and we used the cumulative number of cases over the course of the epidemic to plot P, but one could also use the instantaneous number of cases to obtain a time-dependent probability rate.

3.1. Contrast between fully vaccinated or unvaccinated populations

We use a traditional deterministic SIR model of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), in time units in which the mean infection time is 1. Mathematically, this is

where R0 is the basic reproduction number (assumed greater than one for an epidemic to happen), S(t) is the susceptible proportion of the population, with S(0)=1, and I(t) is the infected proportion of the population. The SIR dynamics can be integrated up to find the total number of infections in the population

where W is the Lambert-W function.

In the case of a vaccinated population, the SIR dynamics are simply modified by the rescaling R0 -> R0θSθI where θS , θI < 1 are the adjusting multiplicative effects on the susceptibility and infectivity rates, respectively, as in Gog et al. [3]. The total number of infected individuals, should the whole population be vaccinated, is ow

with the caveat that if θSθI <1/R0 vaccination would prevent the outbreak from taking over (as the effective R number would be less than one).

3.2. Variable vaccination coverage

We extend the deterministic compartmental SIR to separate between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. We assume that vaccination occurs before the epidemic, and in a fraction c of the population. The vaccinal immunity from the vaccine is assumed to be “leaky” rather than polarised, resulting in reduced susceptibility and transmissibility as described by the ODE system:

Noting that

the model can be integrated up in a similar way than in the standard SIR model. The final number of susceptible individuals in the population, Sf is given implicitly by

We find Sf numerically from this equation The number of cases in unvaccinated individuals is Nunv=Rf = 1-c -Sf , while the number of cases in vaccinated individuals is

4. Results

4.1. Tradeoff between escapiness effect and transmission blocking

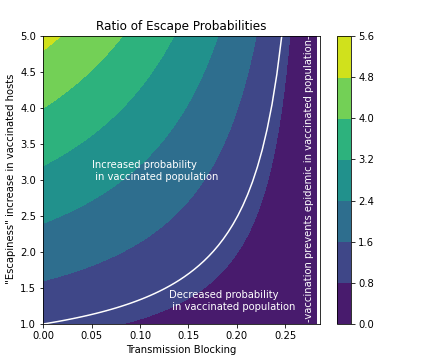

Comparing the probability of escape in the fully unvaccinated and fully vaccinated populations, we find if the evolutionary pressure is larger in a fully vaccinated population or in an, otherwise equal, fully unvaccinated one. This depends on the values of the escapiness effect θE and transmission blocking 1-θSθI, as shown in the contour plot below.

Clearly, it is always best to vaccinate (regardless of the escapiness effect) when transmission blocking is enough to prevent the epidemic, so the maximum escapiness effect that keeps the evolutionary pressure constant (white curve in the contour plot) becomes larger and larger (tending to infinity) as the transmission blocking reaches this value. It also always better to vaccinate (regardless of transmission of blocking) when the escapiness effect is below one (meaning vaccination reduces escapiness).

4.2 Most risky vaccination coverage

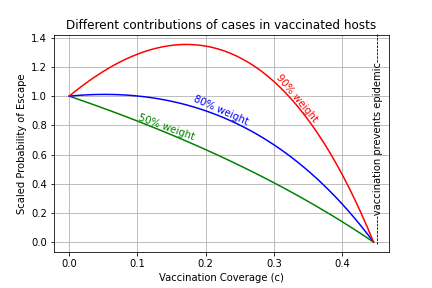

The vaccination coverage (proportion of the population vaccinated) that gives the maximum evolutionary pressure depends on the escapiness effect θE.

- If the escapiness effect is low enough, even if above 1, the reduction of total cases by vaccine transmission blocking at any level of vaccination coverage is enough to outweight the potential increase in number of cases in vaccinated individuals. Hence. the evolutionary pressure decreases as we increase the vaccination coverage, and when enough population has been vaccinated, the outbreak would not become and epidemic and so there would be no evolutionary pressure.

- When the escapiness effect is large enough, meaning that the cases in vaccinated individuals (breakthrough infections) drive evolution, vaccination reduces or increases the evolutionary pressure depending on the vaccination coverage:

- If the vaccination coverage is large, transmission blocking reduces the overall number of cases sufficiently to also decrease escape pressure.

- If the vaccination coverage is small, an increase in the proportion of vaccinated population is leads to more cases in vaccinated individuals, which contribute a lot to the overall mutation probability while the reduction in the cases in unvaccinated individuals is not enough to reduce the overall escape probability.

- Altogether, this means that the probability of mutation at the population level initially increases as we start vaccinating, but after reaching a maximum at an intermediate level of vaccination, it starts to decreases for larger vaccination coverages. There is no chance of an escape variant arising when the enough hosts in the population have been vaccinated to prevent the epidemic.

5. Discussion

In this investigation, we have defined a parameter (the escapiness effect) that measures the evolutionary pressure exerted by vaccines at the within-host level, relative to no vaccination. We have used a simple mathematical model to understand how the population-level evolutionary pressure (i.e, the chances of a vaccine variant) depends on the escapiness effect.

First, we have shown that highly effective vaccines can reduce the risk of an escape variant arising, despite a potentially large escapiness effect, by means of transmission blocking. For COVID-19, which motivates this study, we have good estimates of the vaccine efficacies (VEs) for susceptibility, transmissibility, severity, etc. However, it is unknown the value of the escapiness effect, and so it is difficult to answer the question of whether a vaccine escape variant is more likely to come from a vaccinated or unvaccinated country. The exception is when the vaccine is so effective that the pathogen does not spread into the population: in this case, a mutation cannot occur regardless of the escapiness effect because nobody is infected.

Secondly, we have found that whether vaccination is dangerous from an evolutionary point of view depends on the escapiness effect and in the vaccination coverage. When the escapiness effect is low, it means that cases in vaccinated individuals do not contribute significantly more to the escape pressure: we simply want to reduce the total number of cases and hence the more vaccinated population, the less chances of a variant arising. However, if the escapiness effect is large, a trade-off arising: intermediate vaccination levels are the most dangerous, because they allow for a significant number of cases in the vaccinated hosts without having reduced enough the total cases. This trade-off is analogous to that described at the within-host level in “Phylodynamics” [4], where at intermediate immunity strength there is enough selection pressure and enough viral load, reaching the highest level of “adaptation rate” possible.

We have focused on a transient epidemic in a well-mixed homogenous population, using a deterministic SIR model with vaccination occurring before the start of the epidemic, without waning of either natural or vaccinal immunity. For the plots and analytic results shown, we have assumed that vaccinal immunity is “leaky”, but we have repeated them with “polarised” vaccinal immunity (meaning that a proportion of the vaccinated hosts is fully immune to the disease, while the rest are fully susceptible) and obtained the same qualitative results (not shown). Qualitatively, we expect these results to generalize to other models, as long as cases in unvaccinated hosts still contribute to the evolutionary pressure, and vaccination is imperfect yet able to prevent the epidemic if a sufficient proportion of the population is vaccinated. For example, we added waning immunity to our model with polarised vaccinated immunity, and showed analytically that at the resulting endemic equilibrium the probability of evolutionary pressure has a similar qualitative behaviour as a function of vaccination coverage and escapiness effect.

This model assumes that vaccination has occurred before the start of the epidemic, and that there’s no other type of existing immunity in the population. Further work could consider vaccination occurring at a continuous rate throughout the epidemic, or instantaneously at a single moment some time after the epidemic started. More generally, we have only studied the cumulative probability of infection (using analytic expressions for the final sizes of the epidemic), but not how this probability rate changes over time. Other than by the number of active cases, this time-dependent probability P(t) would also depend on the size of the still susceptible individuals (reducing the chances of the new variant taking over the existing one through stochastic extinction or even bringing the effective R number below 1) and on the host’s viral load as a function on time since infection (which would lag P(t)). Furthermore, since there is no waning of immunity, the epidemic in our model is transient and does not reach and endemic state. We could include waning of immunity, either vaccinal or natural, and allow for reinfections of individuals, which could also contribute to the vaccine escape pressure by having a different (or equal) level of escapiness. As the world reaches substantial levels of immunity against COVID-19 with strong evidence for its waning and the pandemic approaches endemicity, these questions become more significant in answering the question of which country is more likely to produce a highly antigenic variant: a mostly vaccinated one or a mostly unvaccinated one? Another factor that could play an important role and that the population homogeneity of our model neglects is that hosts with a weakened immune system -which are likely to have the infection for a very long time-, like HIV patients, could have a disproportionately large probability of generating an escape variant, so future models could consider them separately.

References

- Cobey et al. Concerns about SARS-CoV-2 evolution should not hold back efforts to expand vaccination. Nature Reviews Immunology 2021

- Thompson et al. SARS_CoV-2 incidence and vaccine escape. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2021

- Gog et al. Vaccine escape in a heterogenous population: insights for SARS-CoV-2 from a simple model. Royal Society Open Science 2021

- Grenfell et al. Unifying the Epidemiological and Evolutionary Dynamics of Pathogens. Science 2004

Email: mag84@cam.ac.uk , Maria A. Gutierrez

Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics (DAMTP) & King’s College.

Acknowledgements: Prof Julia Gog OBE (PhD supervisor) and Gates Cambridge (Scholarship)

Click here for poster display. (Design partially inspired by this video)